Phytoplankton Imaging

Continuous phytoplankton monitoring (especially for Harmful Algal Blooms (HABs) is an essential for providing valuable data on the factors contributing to the formation and persistence of phytoplankton blooms, facilitating a better understanding of their ecology and enabling more timely interventions and development of effective management strategies in the case when HABs are present. Many monitoring efforts are highly time consuming and lack the proper temporal resolution for tracking potential HABs that often bloom and bust in a matter of 1-2 weeks. Moreover, response monitoring is limited by staff field time and funding, and critically the amount of time it takes to count samples via standard microscopy

Automated phytoplankton imaging units can help detect blooms in areas of concern and serve as early warning systems through high-temporal sampling resolution and the ability to analyze discrete samples with high throughput. Funded by an NSF FSML collaborative research grant (2022966), collaborators at the UMCES HPL lab (Drs. Greg Silsbe, Sairah Malkin, Jaimie Pierson, and Matthew Grey) and myself developed PhytoChop, a phytoplankton observatory on the Choptank River, a meohaline tidal sub-estuary of the Chesapeake Bay.

phytoplankton observatory on the Choptank River, a meohaline tidal sub-estuary of the Chesapeake Bay.

The PhytoChop Coastal Observatory is an advanced autonomous instrument array designed to monitor the composition and photosynthetic activity of the phytoplankton community along with water column nutrient and optical properties, over long durations at high frequency. The key components of PhytoChop are an Imaging FlowCytobot (IFCB) and a fast repetition rate fluorometer (FRRF), plumbed in line with two water quality monitors. The IFCB generates high resolution images of plankton containing photosynthetic pigments (more below).

The FRRF measures photosynthetic efficiency of the entire phytoplankton community. This integrated array will enable a deeper understanding of the ecological factors that govern phytoplankton community assembly and activity within a subtropical and strongly seasonal system, at time scales ranging from cellular division to seasonal succession. Current images can be found on this data dashboard.

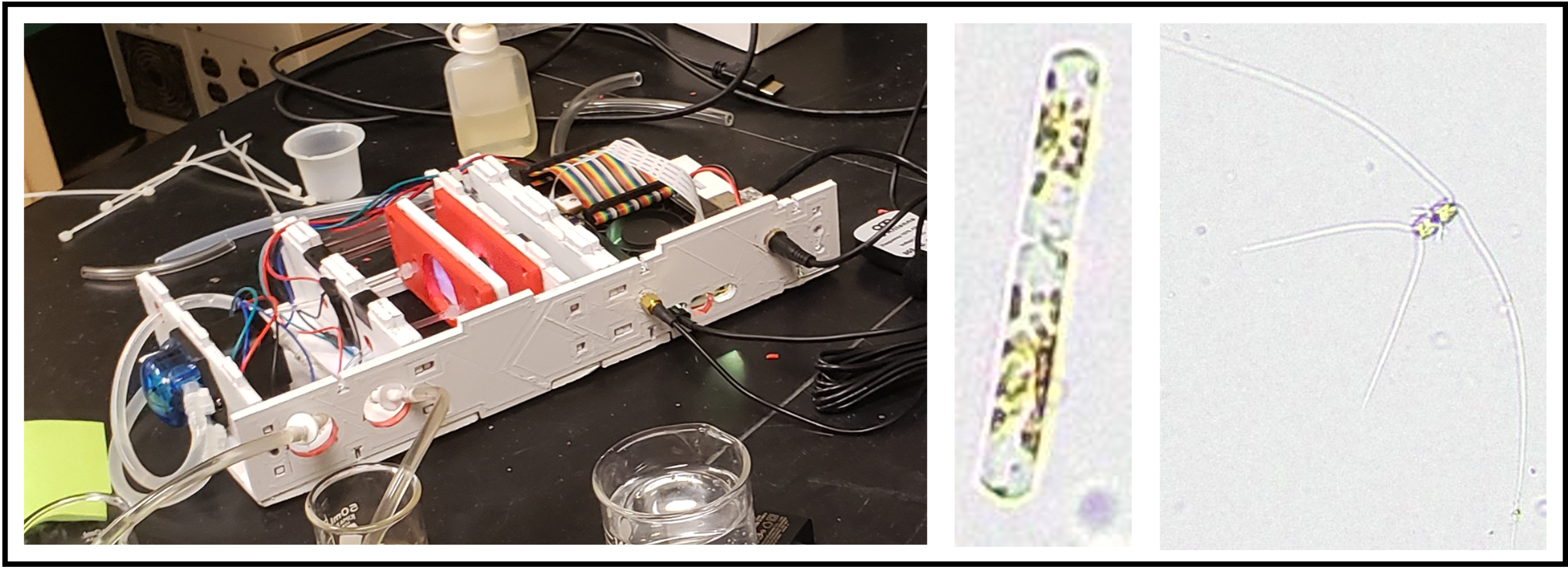

Led by SMCM alum, Matthew Varelli (Class of 2021), the Brownlee lab built a PlanktoScope,

a low-cost, open hardware and open software instrument. PlanktoScope is a portable and user-friendly imaging system that enables rapid field-based monitoring of phytoplankton, including harmful algal species. This handheld device utilizes a built-in camera and high-resolution optics to capture images of phytoplankton cells in water samples. The images can be instantly analyzed using smartphone-based applications or transferred to a computer for further analysis. PlanktoScope provides a cost-effective and accessible solution for HAB monitoring, particularly in remote or resource-limited areas. Its simplicity and ease of use make it an ideal tool for citizen science initiatives and community-based monitoring programs, empowering local stakeholders to actively participate in HAB surveillance and reporting.

The utility of these instruments is reliant on an expertly trained image library and a machine learning pipeline to classify this imagery. Unfortunately, extant image libraries that encompass the diversity of phytoplankton species present in Chesapeake Bay do not exist and require several years of data and taxonomic expertise to train the imagery. The Brownlee lab is currently pursuing this area of research.

Additionally, I am a member of an NSF OCB (Ocean Carbon & Biogeochemistry) office funded working group called Observational Phytoplankton Operations (OPO) to create “Best Practices” for the community utilizing phytoplankton imaging instrumentation (PIIs).

Utilizing new tools to detect the mixotrophic “middle-ground”

In nature, a long held paradigm classifies organisms that make their own food as producers (ex. Plants) and those that obtain their energy externally as consumers (ex. Animals). But organisms have adapted to challenge this model with a metabolic lifestyle called mixotrophy that mixes plant and animal nutrition. While terrestrial mixotrophy is rare, Venus flytraps provide a perfect example of how a single organism can obtain their energy and nutrition from various sources. Venus flytraps produce their own energy from the sun through photosynthesis like typical plants, but they also consume insects for supplemental nutrition. This allows an organism to be particularly competitive when one of those sources of energy is limited. As it turns out, it is increasingly recognized that this seemingly rare feeding strategy is in fact common within many of the smallest microscopic organisms in the ocean and has been long recognized. But what scientists don’t have a good handle on is how these ‘mixotrophic’ organisms affect food-web structure and function and thus integration into food web models is difficult. This is largely due to the inability to correctly attribute this lifestyle to organisms in their natural samples. Currently, the standard for detecting mixotrophy is either observing the presence of certain types of machinery: chloroplasts for photosynthesis or a food vacuole as indication of feeding.

My current work aims to utilize comparative transcriptomic tools to study how gene expression changes due to various metabolic lifestyles. While these techniques have been more commonly utilizing for mixotrophic nanoflagellates, currently, I am exploring the potential for transcriptomic analyses to be used to identify trophic modes of dinoflagellates in culture.

The unique gene expression signatures may provide a distinction between mixotrophs and those living as plants or animals . I am currently using a mixotrophic dinoflagellate, Heterocapsa rotundata, which is commonly found in the Chesapeake Bay as my model organisms to test these hypotheses. In collaboration with SMCM alum, Bryce Easterly (Class of 2023), we induced mixotrophic activity in H. rotundata under low light conditions. We found increased ingestion rates under low light levels. We are currently analyzing the transcriptomic equences using the Alexander lab’s (WHOI) eukrythmic pipeline. Based on results from culture experiments, future work includes environmmental metatranscriptomics of H. rotundata in the St. Mary’s River.

Along with SMCM students (Haley Roche, class of 2025) and Madison Long (class of 2024), I am also exploring temperature and salinity induced mixotrophy on cultures of H. rotundata.

I was a member of an NSF OCB (Ocean Carbon & Biogeochemistry) office funded working group called Mixotrophs and Mixotrophy (M&M). Our most recent paper can be found here, where we provide suggestions future avenues of research in the field.

Wintertime ecology in the Chesapeake Bay

Currently I am assessing the in situ heterotrophic activity among multiple mixotrophs across seasons in Chesapeake Bay (with emphasis on the important, but woefully undersampled winter). The Chesapeake Bay exhibits high variation in environmental conditions and biological processes to provide a valuable stage for studying in situ mixotrophic processes seasonally and subsequently put in context their responses to longer-term trends associated with environmental and climate change. In the winter, a chlorophyll maximum develops in a low light environment, at which time dinoflagellates dominate the phytoplankton community. Mixotrophy is thought to be an essential strategy for these dinoflagellates to dominate in the winter. In collaboration with St. Mary’s College of Maryland (SMCM) students (Chandler Williams, Class of 2023), I am investigating these dinoflagellates (primarily Heterocapsa rotundata and Prorocentrum minimum) through bacterial grazing experiments during bi-monthly sampling of the St. Mary’s River from November – March.

The natural history of ciliates

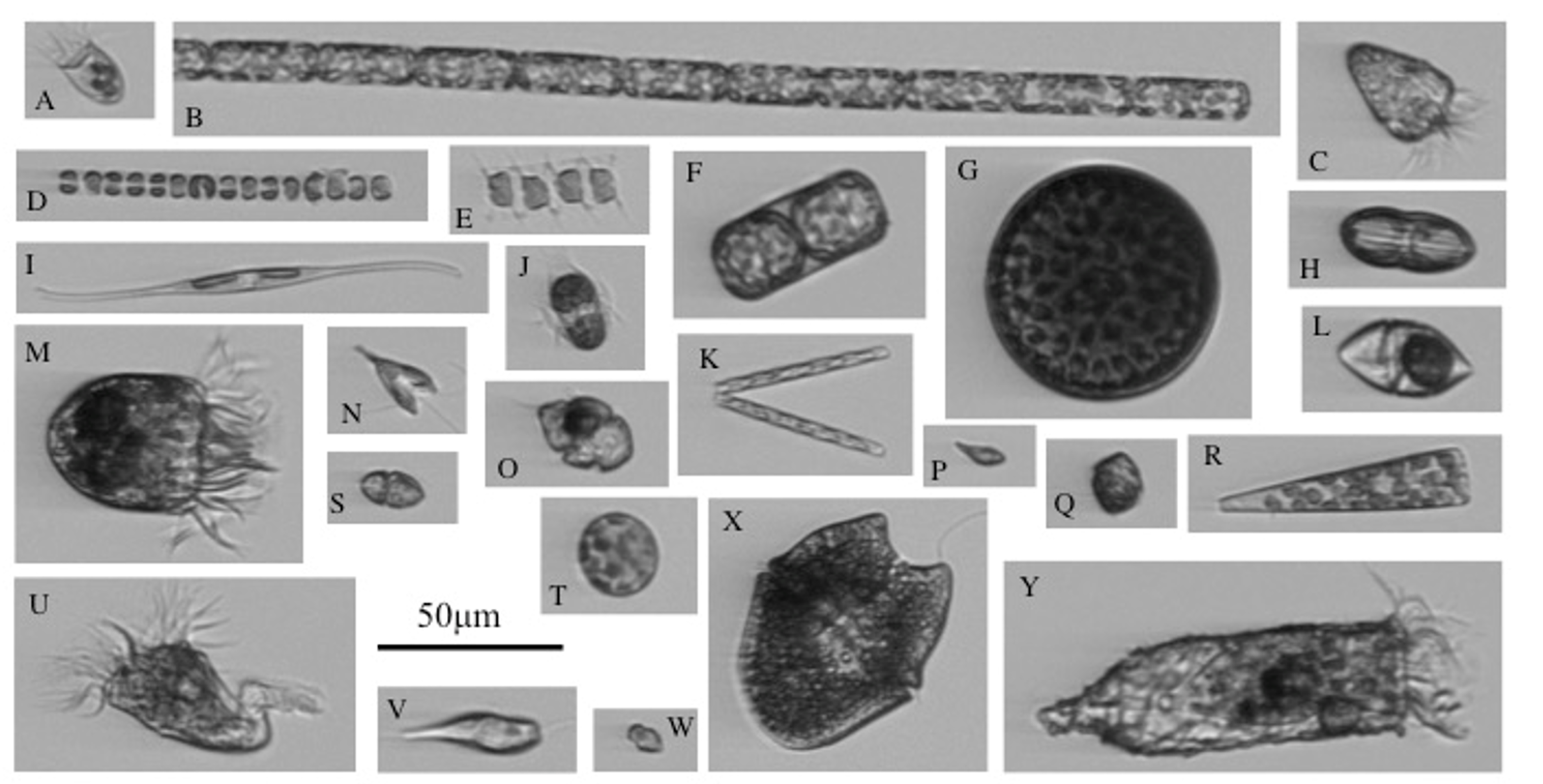

As a PhD student, I investigated the community dynamics of marine ciliates on the New England Shelf. Ciliates are traditionally difficult to quantify due to difficulties in collecting, culturing, and observing these often-delicate cells. To understand ciliate community dynamics, I utilized data obtained from a custom-built, automated, submerged imaging flow cytometer, Imaging FlowCytobot (IFCB) (developed by Drs. Rob Olson and Heidi Sosik, of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) deployed at the Martha’s Vineyard Coastal Observatory (MVCO) (See the time series of all plankton here!).

As a PhD student, I investigated the community dynamics of marine ciliates on the New England Shelf. Ciliates are traditionally difficult to quantify due to difficulties in collecting, culturing, and observing these often-delicate cells. To understand ciliate community dynamics, I utilized data obtained from a custom-built, automated, submerged imaging flow cytometer, Imaging FlowCytobot (IFCB) (developed by Drs. Rob Olson and Heidi Sosik, of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) deployed at the Martha’s Vineyard Coastal Observatory (MVCO) (See the time series of all plankton here!).

This instrument obtains not only high-resolution images of chlorophyll-containing ciliates, but hourly measurements of cell abundance, cell size, and subsequently cell biovolume and biomass. To study and understand a more complete ciliate community beyond those exhibiting herbivory, I developed an updated Imaging FlowCytobot (IFCB-S) modified with automated staining capabilities. Not only were some cell types detected that were not previously, but the comparison of fluorescence properties between staining and non-staining offered insight into the seasonal feeding habits of protist micrograzers. I also found that with IFCB-S, cell abundances were consistently similar to or higher than counts from manual light microscopy indicating that capturing cell abundances with a live application may be more accurate than traditional sampling and preservation.

Molecules and morphology: integrative taxonomic approaches

A large part of my interests involve the development of innovative, integrative tools to study aquatic protists. During my thesis, I combined morphological information from IFCB with genetic techniques to understand temporal changes of community structure. While morphology is a standard method for identifying many ciliates, DNA sequencing has provided new insight into diversity, predator-prey interactions and discrepancies between morphologically defined species and genotypes. I used high-throughput sequencing (HTS) to explore the genetic seasonal community change of tintinnid populations, including both chlorophyll-containing and non-chlorophyll-containing taxa. With their distinct lorica characteristics, tintinnids allowed a direct comparison between IFCB and HTS detection in this study.

I found many species and genera of tintinnids for which morphotype and genotype displayed high congruency. In comparing how well temporal aspects of genotypes and morphotypes correspond, we found that HTS was critical to detect and identify tintinnid genera not efficiently captured with the IFCB.

I extended this work to explored seasonal patterns of subclades within the mixotrophic Mesodinium rubrum/major species complex. The M. rubrum/major subclades have historically been associated with various cell sizes. Despite numerous observations of genetic diversity and size structure plasticity, the response of these two characteristics to seasonal environmental variation has not been rigorously characterized. Integrating morphology from IFCB and sequencing allowed for detection of M. rubrum/major subclades associated with seasonal temperature niches, but not always unique size distributions. These results suggest the interplay of genetic and physiological factors regulating size structure/temperature relationships for the M. rubrum/major species complex.

The M. rubrum/major subclades have historically been associated with various cell sizes. Despite numerous observations of genetic diversity and size structure plasticity, the response of these two characteristics to seasonal environmental variation has not been rigorously characterized. Integrating morphology from IFCB and sequencing allowed for detection of M. rubrum/major subclades associated with seasonal temperature niches, but not always unique size distributions. These results suggest the interplay of genetic and physiological factors regulating size structure/temperature relationships for the M. rubrum/major species complex.